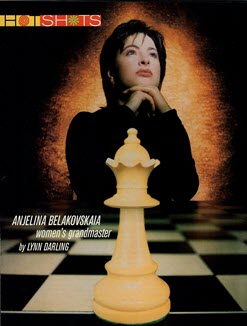

By Lynn Darling. Photograph by Joseph Pluchino.

DESTINY TAKES MANY DISGUISES, THOUGH ONLY A JOKER would equate the New Jersey Turnpike with the Yellow Brick Road. Yet where most other travelers have seen only smokestacks, frayed nerves and exit signs, Anjelina Belakovskaia found her way home.

Staring out a car window, just off a plane from Ukraine six years ago, she was dazzled by the simple logic of America in motion. “The highway said, ‘Here’s the way. Everybody just go,’ ” she says, her voice softening at the memory. “Everything depends on you-if you go fast, if you go slow, if you get there, if you don’t, it’s all up to you.” She laughs. “Of course, then I didn’t know about speed limits.”

If Belakovskaia, now 28, has learned anything about slowing down since her arrival in the U.S., she doesn’t let it show. Her version of the immigrant’s odyssey has taken her from slicing watermelon at a fruit stand in Brooklyn to trading currency on Wall Street, from hustling chess games in Manhattan’s Washington Square Park to her current position as the reigning U.S. women’s chess champion. Like a teenager on a skateboard, Belakovskaia surfs through life amused but hardly surprised by her stops along the way-be it a movie set or, these days, an elementary school classroom in Brooklyn, where she lights a fire under seven-year-olds dreaming of captive queens.

It is another long afternoon at the end of the school year at P.S. 217 in Brooklyn, a time when, if a teacher’s not careful, a child’s brain can turn into a vacant lot. But Margaret Jansen’s classroom is a hive of activity: Second graders cluster around tables, observing chess moves with a rising excitement. The competition is so keen that Jansen’s calls for order are barely acknowledged. “Put your hands down on the desk,” she says. “Even if you just took the queen, you must stop playing!”

Calm is restored when a young woman in tight black jeans, an equally tight striped T-shirt and high heels walks to the front of the classroom and flicks a cascade of dark curls away from her face with a hand punctuated by long red nails. (Belakovskaia’s artlessly flamboyant appearance has not been lost on her students; as a class project they wrote letters to Mattel, trying to interest the company in marketing a chess-playing doll they called, ”Anjelina 2000, the Barbie with Beauty and Brains.”)

“Today is our last lesson,” Belakovskaia tells them. “I want to make sure that you know how to win the game. That is most important.” That philosophy belies her own approach to chess, as well as to life. To Belakovskaia, both are games to be played with gusto while others tally the wins and losses. “She is a very aggressive player,” says Alex Yermolinsky, a grandmaster and the U.S. men’s champion. While many players favor well-known strategies or positions, Belakovskaia is inventive and, says Yermolinsky, “never afraid.”

Sitting in her attic apartment in Brighton Beach, the Brooklyn community known as Little Odessa because of the 150,000 immigrants from the former Soviet republics who have settled there since 1989, Belakovskaia makes her journey sound simple, though it couldn’t have been. She stepped off the plane from Odessa with $100 and a tourist visa in her pocket. Her plan was to compete in the World Open in Philadelphia, spend a couple of weeks in the U.S., then head home. That plan changed her first day here. She didn’t know any English, or anyone who spoke English, or what she would do for a living, or even where she would live-but she knew she wanted to stay. “I thought, What have I got to lose?” she recalls. “I had a return ticket. I could always go back home.”

Belakovskaia and her brother Leonid grew up in Odessa’s febrile mix of artists, musicians and scholars. Their father, Mikhail, was a college professor and their mother, Lilia, taught elementary school. “In Odessa every parent thinks their child is genius,” Belakovskaia says. “As soon as you turn six, you take some kind of lessons.” By the time she was 11, Belakovskaia was the highest-rated player her age in Odessa and thoroughly fascinated by chess. “It was interesting to find the best way around the board, to see what I could create, to solve a problem,” she says. “I liked the challenge, the logical thinking.”

Challenges have been plentiful since. After Belakovskaia competed in the World Open in 1991, she was broke, so she made her way to Brighton Beach, where a fellow immigrant gave her a room in which to stay. Someone else gave her subway directions to Washington Square, where, she was told, she might earn money playing chess. Her first words of English were, “Five dollars a game.” Her hustling paid its biggest dividend when she was paid $2,000 to be an extra in the 1993 movie Searching for Bobby Fischer, which was filmed in Washington Square.

Since then she has had about 20 jobs, including painter, waitress, fruit seller and espresso maker. Her bluffing ability was most helpful when she interviewed for an internship as a currency trader on Wall Street. The interviewer showed her a graph, which charted the value of deutsche marks against dollars, and wanted to know if the deutsche mark was going up or down. Belakovskaia saw that the graph was headed in a northerly direction, but, “I figured it was like the logic for chess: Don’t look just straight ahead for the answer, analyze the other possibilities. So I said, ‘Down,’ and I was right.” She got the job.

The classes Belakovskaia teaches at P.S. 217 and elsewhere have given her a measure of financial stability that enables her to play tournament chess. (She is one of four women’s grandmasters in America.) But her passion is costly: Money earned in the winter goes for traveling and entering tournaments in the summer. Her commitment even cost her a serious relationship, which fizzled when her boyfriend made her choose between him and a tournament in Las Vegas. “I think I look for another grandmaster next time,” she says.

Belakovskaia tells these stories with a shrug, but she clearly has an inexhaustible will. And she continues to believe in the roll of the dice, in the sheer joy of goosing fate. In life, as in chess, she says, “a lot of people are losers because they take it too seriously. For me it’s a game. If I lose, then I will win next time.”

Leave a Reply